A Tale of Performance - JavaScript, Rust, and WebAssembly

• Tyler WilcockWelcome to another Widen engineering blog post! Today, we’re going to embark on a journey of optimization. We’ll compare and contrast multiple approaches to solving a simple performance problem, one of which being the web’s newest and shiniest addition, WebAssembly.

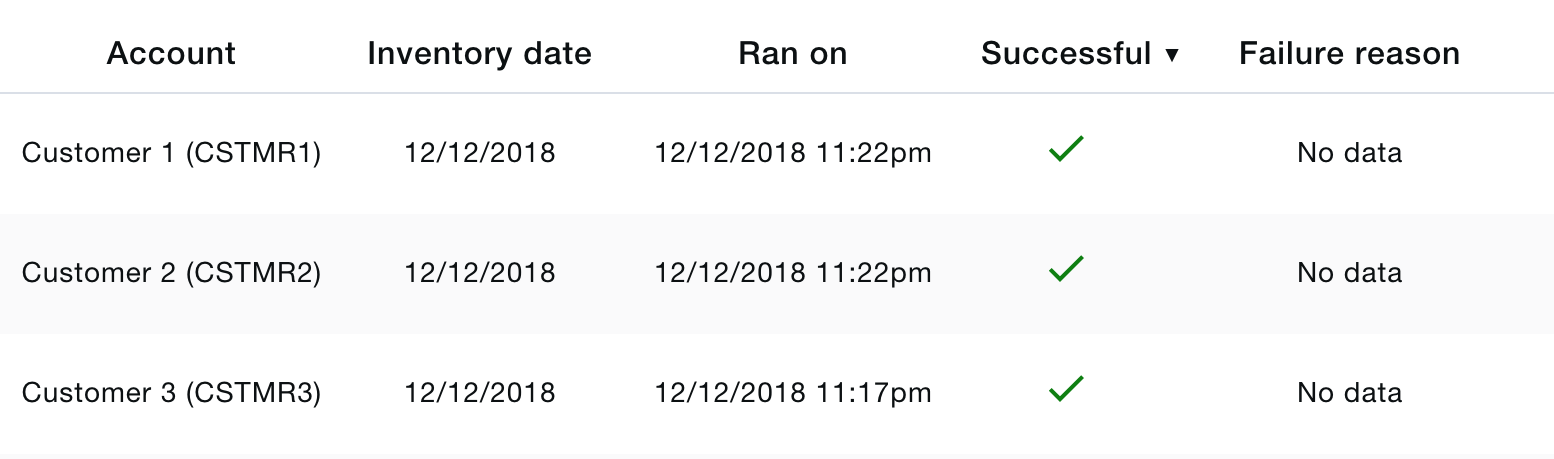

Widen is a technology company, and like many other technology companies we do a lot of presentation (and, therefore, sorting) of data. Recently, I came across one of our internally-facing apps that has a table of data representing the status of certain inventory operations. Users have the option to sort by a variety of fields in this table, such as the date and time the inventory operation ran, whether or not it was successful, the name of the account in question, and more.

This is a useful tool to have! However, there is one problem - the sorting for this table is done client-side, and even when we limit it to retrieving only 1,000 results from the database, there is a noticeable (200-300ms) delay when sorting some of the more complex fields. Is this acceptable for an internal tool? Probably. But I, like many of you, appreciate fast things, so let’s see how speedy we can make this thing go.

The starting point

The current sorting algorithm is written in JavaScript and uses various JavaScript APIs and libraries, such as String.localeCompare and the moment.js date library, to compare items when determining order. Here’s what it looks like:

const swapIfDesc = (comparisonResult, sortDirection) => {

if (sortDirection === SortDirection.DESC) {

return comparisonResult === 1 ? -1 : (comparisonResult === -1 ? 1 : 0)

}

return comparisonResult

}

const cmp = (a, b) => {

return (a > b) ? 1 : (a < b) ? -1 : 0

}

const sortInventoryRuns = (sortBy, sortDirection) => {

return this.props.inventoryRuns.sort((rowA, rowB) => {

// These end up looking something like 'Widen (WIDEN)',

// 'Customer 1 (CSTMR1)', etc.

const accountNameA = ...

const accountNameB = ...

switch (sortBy) {

case TABLE_FIELDS.accountProperName: {

return ...

}

case TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn: {

return ...

}

case TABLE_FIELDS.wasSuccessful: {

const wasSuccessfulComparison = cmp(rowA[sortBy], rowB[sortBy])

if (wasSuccessfulComparison === 0) {

const isoA = rowA[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn] ?

moment(rowA[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).toISOString() :

' '

const isoB = rowB[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn] ?

moment(rowB[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).toISOString() :

' '

const ranOnComparison = cmp(isoA, isoB)

const result = ranOnComparison === 0 ?

accountNameA.localeCompare(accountNameB) :

ranOnComparison

return swapIfDesc(result, sortDirection)

}

return swapIfDesc(wasSuccessfulComparison, sortDirection)

}

...other case statements...

default:

console.error(

`Unexpected default when sorting inventory runs: ${sortBy}`

)

return 0

}

})

}

We’re going to focus on the “was successful” sort in this post, as we could potentially be sorting by three different fields (operation success, the “ran on” date, and the account name) to get a consistent post-sort result.

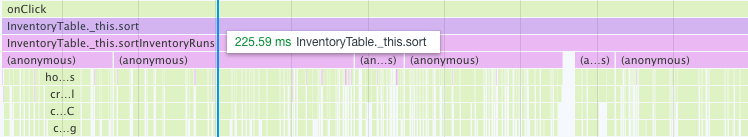

We will begin with the most important step of performance tuning: a baseline. Fortunately, all modern browsers have some form of a performance measurement tool. Here’s a snippet of Chrome’s in action against our code:

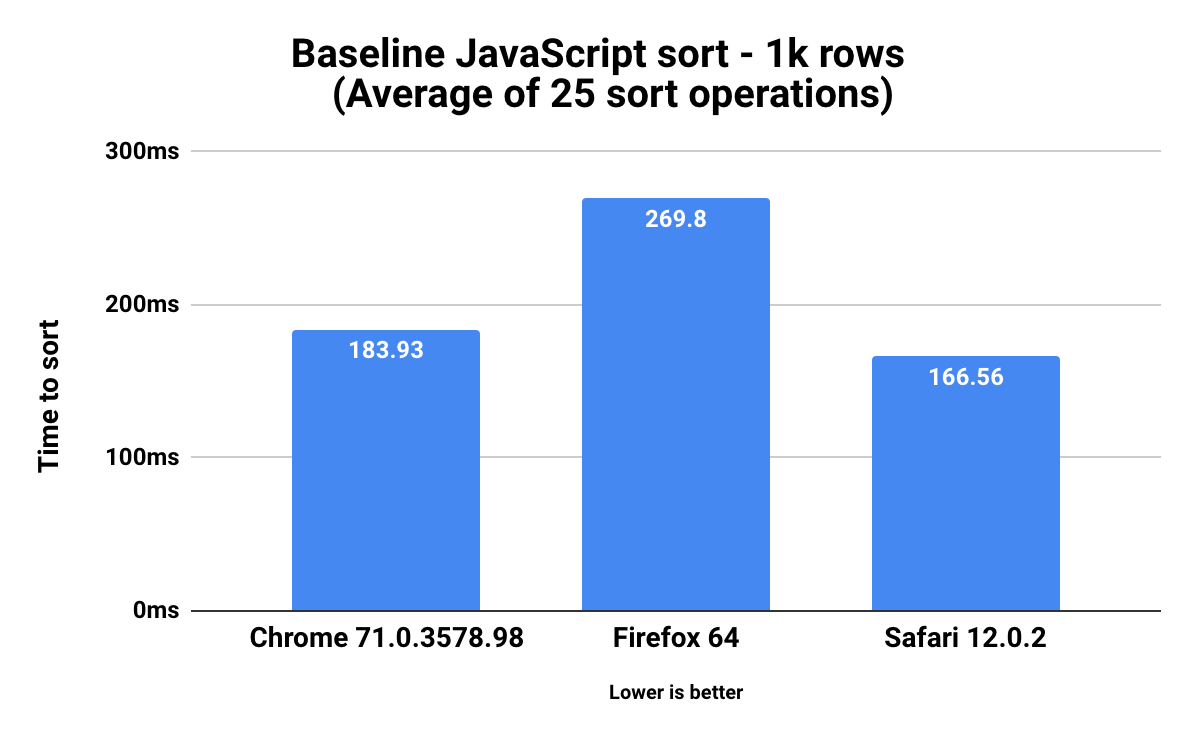

However, for this experiment we want to test against multiple browsers (namely Chrome, Firefox, and Safari), so from here on out we will be looking at graphs. Without further ado, here is the baseline performance of our initial JavaScript “was successful” sort in each browser:

Before we move on, there are some things I want to mention about this measurement, and all future measurements:

- Unless otherwise noted, the code was built in release mode to ensure all possible optimizations were applied.

- The recorded time is the average of 25 repeated sort operations.

- The averages only include time spent in our

sortInventoryRunsfunction. So, for example, any work that React does post-sort to re-render our table is not included in these benchmarks. - All measurements were taken with the app running locally on my 2.8GHz-configured 2014 MacBook pro. I am using macOS Mojave v10.14.2.

- In Chrome and Safari, I used the built-in devtools to get exact runtimes for each sorting operation. In Firefox, I used this tool.

Keep it simple, stupid (KISS)

Reviewing our algorithm for sorting the “was successful” table field, we compare table rows in up to three different ways:

- The success of the inventory operation

- The date and time the inventory operation ran

- The name of the account for which the inventory operation was performed

The first comparison is very cheap; the only possible values are true or false. The second operation is likely the most expensive, since we use moment.js to ensure our dates are in ISO 8601 format before attempting to lexicographically compare them. As described in this StackOverflow post, the ISO 8601 formats were designed with lexicographical comparison in mind. What this means in practice is that we are able to use the built-in language comparison operators, such as < and >, to determine whether one date string is before or after another. The third step in this algorithm requires use of String.localeCompare, which isn’t cheap but is likely far less expensive than the parsing and comparing of dates in step two. A quick peek at Chrome’s flamegraph tool confirms this suspicion. The vast majority of our runtime is spent inside moment constructing our ISO 8601 date strings.

So, in true KISS mentality, let’s first reach for the most obvious solution, the JavaScript Date API. There are a variety of ways to sort valid JavaScript Date objects, one of which being lexicographical comparison with <, > and the like. Also, since this API is a browser built-in, we know that it’s battle tested and written in heavily optimized C++ (or some similarly speedy language). To illustrate this point, we can actually look at the code that powers Date objects in v8 (Chrome’s JavaScript engine). Directly linked is the Date constructor built-in, and throughout the rest of that file, you’ll see built-ins for other familiar functions such as BUILTIN(DateNow) and BUILTIN(DatePrototypeToString).

Rather than directly comparing Date objects, we’ll instead compare the result of each Date’s getTime() function, since doing it that way seems be a bit faster. Here’s what our code looks like now:

const sortInventoryRuns = (sortBy, sortDirection) => {

return this.props.inventoryRuns.sort((rowA, rowB) => {

const accountNameA = ...

const accountNameB = ...

switch (sortBy) {

...other case statements...

case TABLE_FIELDS.wasSuccessful: {

const wasSuccessfulComparison = cmp(rowA[sortBy], rowB[sortBy])

if (wasSuccessfulComparison === 0) {

// Out with the old...

// const isoA = rowA[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn] ?

// moment(rowA[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).toISOString() :

// ' '

// const isoB = rowB[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn] ?

// moment(rowB[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).toISOString() :

// ' '

// const ranOnComparison = cmp(isoA, isoB)

// And in with the new!

const ranOnComparison = cmp(

new Date(rowA[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).getTime(),

new Date(rowB[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).getTime()

)

const result = ranOnComparison === 0 ?

accountNameA.localeCompare(accountNameB) :

ranOnComparison

return swapIfDesc(result, sortDirection)

}

return swapIfDesc(wasSuccessfulComparison, sortDirection)

}

...other case statements...

}

})

}

Furthermore, as you may have noticed from the jsperf link in the previous paragraph, the date strings we get from the database (found in rowA/B[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]) are already in a valid form of the ISO 8601 format, which means they could be lexicographically compared without wrapping them in a Date at all!

Does this mean we should drop usage of Date completely, then? It certainly seems like we could, but using Dates gives us a bit more flexibility in terms of date formats that we can use, as (by convention, not by standard) some browsers support RFC 2822 and various other formats in addition to ISO 8601. This makes it a more robust solution versus direct string comparison, so if it’s fast enough I think it would still be a good route for us to take.

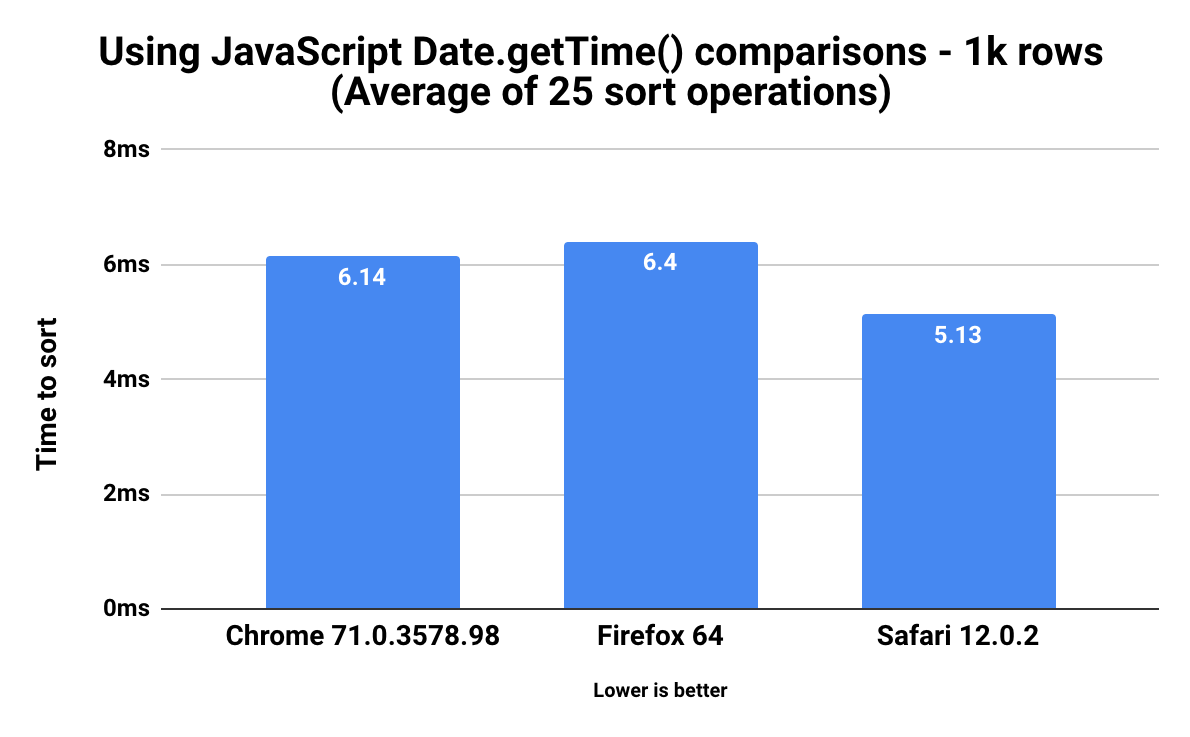

Here are the benchmarks for our Date implementation:

Much better! Versus the baseline implementation, our Date API implementation is 96.6% faster in Chrome (183.93ms to 6.14ms), 97.6% faster in Firefox (269.8ms to 6.4ms), and 96.9% faster in Safari (166.56ms to 5.13ms).

So, we’re done, right?

We certainly could be! We have a fast, simple, and maintainable solution. What more could a developer want? Well, while making this change, I got curious. How would WebAssembly perform in this scenario? It’s unrealistic to think that it would perform better than a native API, but it would be an interesting experiment and could serve as a model for replacing performance-sensitive pieces of code that aren’t fixable with native APIs.

In the remainder of this blog post, we’ll set up a Rust (more on this choice later) stack that is capable of compiling to WebAssembly, replace our date comparison code with a Rust implementation, and then see how it stacks up to our two previous benchmarks.

What is WebAssembly anyway?

For all those who haven’t yet been exposed to WebAssembly, here is what the WebAssembly team has described it as:

WebAssembly (abbreviated Wasm) is a binary instruction format for a stack-based virtual machine. Wasm is designed as a portable target for compilation of high-level languages like C/C++/Rust, enabling deployment on the web for client and server applications.

In addition to the binary format, there is also a textual WebAssembly format (.wat). This allows WebAssembly to be read and edited by humans, since most of us aren’t very good at reading and writing in binary. Here’s a .wat module that exports an add function:

(module

(func $add (param $lhs i32) (param $rhs i32) (result i32)

get_local $lhs

get_local $rhs

i32.add)

(export "add" (func $add))

)

There are quite a few resources out there that go in to more detail about .wat (and WebAssembly in general), so if you’d like to learn more, check out the official WebAssembly webpage or Mozilla’s .wat documentation.

WebAssembly provides several performance advantages over JavaScript - for example, streaming compilation. And probably of equal importance, WebAssembly is here - version 1.0 has shipped and is available in Firefox, Chrome, Safari, and Edge.

Many popular languages can be compiled into WebAssembly, including C, C++, C#, and Rust. In addition, many other languages are working on allowing compilation to WebAssembly, sometimes using external tools like Emscripten.

So, with all these choices, you might be wondering…

Why Rust?

I chose Rust because performance is important for this use case, and as a systems programming language Rust is quite performant. C and C++ offer similar levels of performance, but the key difference is that Rust guarantees thread and memory safety at compile time, whereas other languages either require you to keep track of memory yourself (which can be quite hard) or require costly runtime garbage collection. Rust also has a nice package manager (cargo), an expressive type system, and a spectacular community surrounding it.

Rust is vying to be one of the primary languages for writing WebAssembly-compilable code. They have dedicated a working group towards this goal, and have made some really powerful tools and documentation to help facilitate WebAssembly development. We will be making use of some of these tools later on in this post.

C#, another powerful language, has one major flaw when it’s used to compile to WebAssembly - the runtime. In order to run any C# code as WebAssembly, you must also bring along the C# runtime compiled to WebAssembly, which (as of March 2018) weighs in somewhere around 700kb. This is something the Blazor team is working hard to optimize, so if this piques your interest, do keep an eye out.

Rust does not have this problem. When compiling to WebAssembly, the only code we pay for is the code we end up writing. This idea of zero-cost abstractions is a core tenet of Rust’s design, and the design of libraries fundamental to the ecosystem such as wasm-bindgen for WebAssembly or embedded-hal for embedded systems development.

Setup

Alright, now that we know a little bit more about both Rust and WebAssembly, let’s get our stack set up and get going. Fortunately for us, the Rust WebAssembly team has already assembled a fantastic book detailing the basics of using Rust for compiling to WebAssembly. We’ll be following the setup instructions found there. In short, this is:

- Installing the stable Rust toolchain

- Installing wasm-pack, which will build our Rust into WebAssembly and JavaScript “glue” code using other tools (such as wasm-bindgen) under the hood

- Installing cargo-generate and using it to add the necessary components for Rust and WebAssembly into our existing project

With all these installed, let’s switch to our frontend directory and cargo generate a wasm-pack template.

cd frontend

# when prompted, we'll simply call our project 'rust'

cargo generate --git https://github.com/rustwasm/wasm-pack-template

# remove various generated things we don't need since we have a pre-existing project

cd rust && rm -rf .git && rm .gitignore && rm .appveyor.yml && rm .travis.yml && rm README.md

In the end, this leaves us with a project structure looking like this:

inventory-project/

├── api/

├── app/

├── other pre-existing modules...

└── frontend/

├── other pre-existing directories...

└── rust/

├── Cargo.toml

└── src/

| ├── lib.rs

| └── utils.rs

└── tests/

└── web.rs

We’re in business! Our soon-to-come Rustic WebAssembly functions will live in src/lib.rs, which currently looks something like this:

extern crate cfg_if;

extern crate wasm_bindgen;

mod utils;

use cfg_if::cfg_if;

use wasm_bindgen::prelude::*;

cfg_if! {

// When the `wee_alloc` feature is enabled, use `wee_alloc`

// as the global allocator.

if #[cfg(feature = "wee_alloc")] {

extern crate wee_alloc;

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOC: wee_alloc::WeeAlloc = wee_alloc::WeeAlloc::INIT;

}

}

#[wasm_bindgen]

extern {

// Import the `window.alert` function from the Web.

fn alert(s: &str);

}

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub fn greet(name: &str) {

// Export a `greet` function from Rust to JavaScript that

// alerts a pleasant greeting.

alert(&format!("Hello from WebAssembly, {}!", name));

}

Let’s briefly touch on what’s going on here. Starting from the top, the first interesting thing you might notice is this wee_alloc business. wee_alloc is a memory allocator that is optimized to be as small as possible, which is important on the web because each extra kilobyte directly impacts page load speed. The README for wee_alloc goes into much greater detail on this subject, so check it out for an interesting read.

The next thing of note are the #[wasm_bindgen] annotations, which are provided by the wasm-bindgen crate. Per wasm-bindgen’s own README, it facilitates high-level interactions between WebAssembly modules and JavaScript. Put even more simply, it allows you to “import JavaScript things into Rust and export Rust things to JavaScript.” In our src/lib.rs example above, we could import and call the greet function exactly like we do other JavaScript modules and functions. This is pretty sweet!

wasm-bingen’s usefulness doesn’t stop there, however. It also offers numerous sub-crates, such as js-sys, which provides raw bindings to global JavaScript APIs like String.localeCompare, and web-sys, which provides raw bindings to Web APIs like HTMLDivElement. These crates are designed to be the libc of the web, which is one of many reasons I’m excited for Rust’s potential in the WebAssembly scene.

Time to oxidize

Okay, we have our project set up and know a little more about how our Rust ends up as usable WebAssembly modules. Let’s begin implementing the Rust version of our sorting algorithm. Fortunately, Rust has a solid date/time library called chrono that will allow us to compare dates, so this task becomes very easy.

In our Cargo.toml file, in which we specify our dependencies (among other things), let’s add our chrono dependency. After doing so, Cargo.toml should look something like this:

[package]

name = "wasm"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["Tyler Wilcock <twilcock@widen.com>"]

edition = "2018"

[lib]

crate-type = ["cdylib"]

[features]

default-features = ["console_error_panic_hook", "wee_alloc"]

[dependencies]

cfg-if = "0.1.6"

wasm-bindgen = "0.2"

chrono = "0.4"

# The `console_error_panic_hook` crate provides better debugging

# of panics by logging them with `console.error`. This is great

# for development, but requires all the `std::fmt` and

# `std::panicking` infrastructure, so isn't great for code size

# when deploying.

console_error_panic_hook = { version = "0.1.5", optional = true }

# `wee_alloc` is a tiny allocator for wasm that is only ~1K in

# code size compared to the default allocator's ~10K. It is

# slower than the default allocator, however.

wee_alloc = { version = "0.4.2", optional = true }

And now in src/lib.rs we will add the following code to compare our date strings:

use chrono::prelude::*;

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use wasm_bindgen::prelude::*;

#[wasm_bindgen(js_name = "compareDates")]

pub fn compare_dates(in_date_a: String, in_date_b: String) -> i8 {

let date_a = (&in_date_a)

.parse::<DateTime<Utc>>()

.expect(&format!("couldn't parse date_a - {}", in_date_a))

.date();

let date_b = (&in_date_b)

.parse::<DateTime<Utc>>()

.expect(&format!("couldn't parse date_b - {}", in_date_b))

.date();

match date_a.cmp(&date_b) {

Ordering::Greater => 1,

Ordering::Equal => 0,

Ordering::Less => -1,

}

}

Voila! We have created a function that will take two JavaScript strings, parse them as UTC dates with chrono, and then compare them. We add the wasm_bindgen annotation so that it knows we want to make this function accessible to JavaScript under the name compareDates.

Let’s package up the code into a WebAssembly module so that JavaScript can get at it. This is as easy as running wasm-pack build, which, by default, builds our code with optimizations enabled.

$ wasm-pack build

[1/9] 🦀 Checking `rustc` version...

[2/9] 🔧 Checking crate configuration...

[3/9] 🎯 Adding WASM target...

info: component 'rust-std' for target 'wasm32-unknown-unknown' is up to date

[4/9] 🌀 Compiling to WASM...

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.49s

[5/9] 📂 Creating a pkg directory...

[6/9] 📝 Writing a package.json...

ℹ️ [INFO]: Optional fields missing from Cargo.toml: 'description', 'repository', and 'license'. These are not necessary, but recommended

[7/9] 👯 Copying over your README...

⚠️ [WARN]: origin crate has no README

wasm-bindgen 0.2.21

[8/9] ⬇️ wasm-bindgen already installed...

[9/9] 🏃♀️ Running WASM-bindgen...

✨ Done in 0 seconds

📦 Your wasm pkg is ready to publish at "/Users/twilcock/projects/inventory-project/frontend/rust/pkg".

As you might see from the output above, we have a new directory in our rust/ directory called pkg/, which contains both our WebAssembly module and the JavaScript glue required to use it.

└── frontend/

├── ...

└── rust/

├── Cargo.toml

└── pkg

| ├── package.json

| ├── wasm.d.ts

| ├── wasm.js

| └── wasm_bg.wasm

|

└── src/

| ├── lib.rs

| └── utils.rs

|

└── tests/

└── web.rs

The .wasm file isn’t going to be very interesting. Remember, WebAssembly is a binary format. Let’s look instead look at the glue wasm-bindgen created for us in wasm.js.

/* tslint:disable */

import * as wasm from './wasm_bg';

let cachedEncoder = new TextEncoder('utf-8');

let cachegetUint8Memory = null;

function getUint8Memory() {

if (cachegetUint8Memory === null || cachegetUint8Memory.buffer !== wasm.memory.buffer) {

cachegetUint8Memory = new Uint8Array(wasm.memory.buffer);

}

return cachegetUint8Memory;

}

function passStringToWasm(arg) {

const buf = cachedEncoder.encode(arg);

const ptr = wasm.__wbindgen_malloc(buf.length);

getUint8Memory().set(buf, ptr);

return [ptr, buf.length];

}

/**

* @param {string} arg0

* @param {string} arg1

* @returns {number}

*/

export function compareDates(arg0, arg1) {

const [ptr0, len0] = passStringToWasm(arg0);

const [ptr1, len1] = passStringToWasm(arg1);

return wasm.compareDates(ptr0, len0, ptr1, len1);

}

let cachedDecoder = new TextDecoder('utf-8');

function getStringFromWasm(ptr, len) {

return cachedDecoder.decode(getUint8Memory().subarray(ptr, ptr + len));

}

export function __wbindgen_throw(ptr, len) {

throw new Error(getStringFromWasm(ptr, len));

}

Lots going on here. Let’s start by looking at compareDates. It’s pretty bare, essentially just calling into the .wasm version of compareDates. So, why is it here, and why do we keep referring to this code as “glue”?

To answer this question, there’s something else we need to know about WebAssembly: It currently supports a very limited number of types, namely i32, i64, f32, and f64. This obviously excludes all of the rich types we see in JavaScript, such as strings and objects. You can probably see the issue here. Our dates are represented as strings, not integers or floats, meaning we can’t pass them as is to our WebAssembly module.

wasm-bindgen solves this problem by automatically creating code that takes our rich types, like the string version of our dates, and converts them into types that WebAssembly can work with. We see this in the passStringToWasm function, which takes our string, turns it into bytes, and copies those bytes from JavaScript’s heap into WebAssembly’s linear memory. The act of allocating space for and copying of the bytified version of our string is very expensive, especially when done frequently in small increments (which is, unfortunately, exactly what we’re doing). We’ll see just how expensive this is later on.

Eventually this glue code will not be necessary thanks to the interface types proposal. Among many other things, the interface types proposal provides a standard way to create rich types, such as strings and JSON, when passed some function that can allocate memory (wee_alloc, anyone?). Interface types will also unlock faster than JavaScript DOM access since WebAssembly functions are statically checked and thus do not require the runtime-type checks that JavaScript functions do.

Back to JavaScript

We have successfully created our WebAssembly module and have generated the glue code required to use it. First, let’s import the compareDates WebAssembly function we created in the previous step:

import { compareDates } from '../../rust/pkg/wasm'

Thanks to wasm-pack, importing this function is as easy as doing so from any other module. Now to replace our Date API implementation with compareDates:

const sortInventoryRuns = (sortBy, sortDirection) => {

return this.props.inventoryRuns.sort((rowA, rowB) => {

const accountNameA = ...

const accountNameB = ...

switch (sortBy) {

...other case statements...

case TABLE_FIELDS.wasSuccessful: {

const wasSuccessfulComparison = cmp(rowA[sortBy], rowB[sortBy])

if (wasSuccessfulComparison === 0) {

// Our old `Date` API comparison...

// const ranOnComparison = cmp(

// new Date(rowA[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).getTime(),

// new Date(rowB[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn]).getTime()

// )

// And our new Rust date comparison!

const ranOnComparison

= compareDates(rowA[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn], runB[TABLE_FIELDS.ranOn])

const result = ranOnComparison === 0 ?

accountNameA.localeCompare(accountNameB) :

ranOnComparison

return swapIfDesc(result, sortDirection)

}

return swapIfDesc(wasSuccessfulComparison, sortDirection)

}

...other case statements...

}

})

}

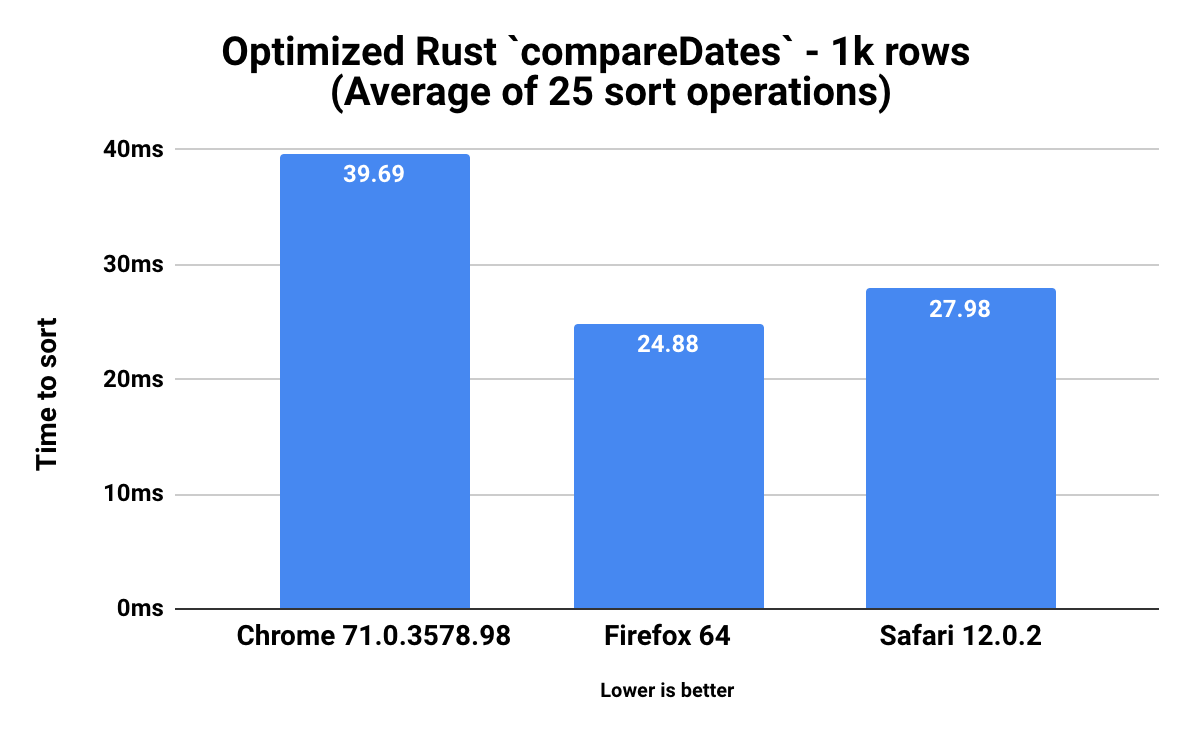

And now for the benchmarks of this newly-oxidized sort implementation. This is with the optimized version of our Rust/WebAssembly code (remember, wasm-pack build optimizes by default).

Not too bad! Versus our initial moment-based implementation, in Chrome we see a 78% improvement (183.93ms to 39.69ms), in Firefox a 90% improvement (269.80ms to 24.88ms), and in Safari an 83% improvement (166.56ms to 27.98ms).

You’ll also notice that the WebAssembly version of our date comparison code is quite a bit slower than our browser-native Date API implementation. Specifically, the WebAssembly version is 85% slower in Chrome (5.95ms to 39.69ms), 72% slower in Firefox (6.96ms to 24.88ms), and 72% slower in Safari (7.72ms to 27.98ms).

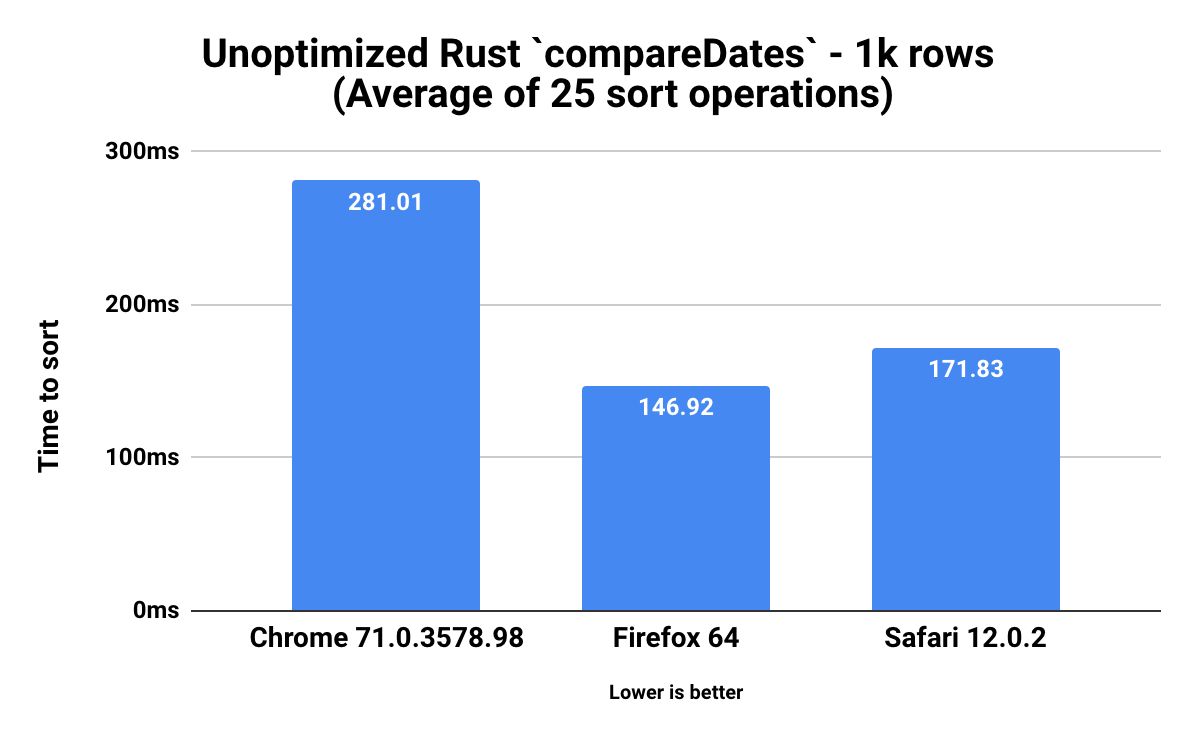

Because I was curious, here are the benchmarks for the unoptimized version of our compareDates function:

While still acceptable for development, this is much slower than the performance of the optimized version, but includes debug info and debug assertions. Versus the optimized version of compareDates, the unoptimized version is 85% slower in Chrome (39.69ms to 281.01ms), 83% slower in Firefox (24.88ms to 146.92ms), and 83% slower in Safari (27.98ms to 171.83ms).

Sweet naivete

Let’s unpack these results a bit. It’s unsurprising that the WebAssembly version is slower than a native browser API, but our results show that it’s significantly slower - 85% slower in the worst case. Why is it so slow?

To answer this question, let’s revisit our discussion about the wasm-bindgen’s passStringToWasm function. This function takes our JavaScript strings, turns them into bytes, and then copies those bytes from JavaScript’s heap into WebAssembly’s linear memory. This operation is very expensive, so much so that the Rust and WebAssembly book has defined some guidelines that explicitly advocate for doing it as little as possible:

When designing an interface between WebAssembly and JavaScript, we want to optimize for the following properties:

1. Minimize copying into and out of the WebAssembly linear memory. Unnecessary copies impose unnecessary overhead.

2. Minimize serializing and deserializing. Similar to copies, serializing and deserializing also impose overhead, and often impose copying as well. If we can pass opaque handles to a data structure — instead of serializing it on one side, copying it into some known location in the WebAssembly linear memory, and deserializing on the other side — we can often reduce a lot of overhead. wasm_bindgen helps us define and work with opaque handles to JavaScript objects or boxed Rust structures.

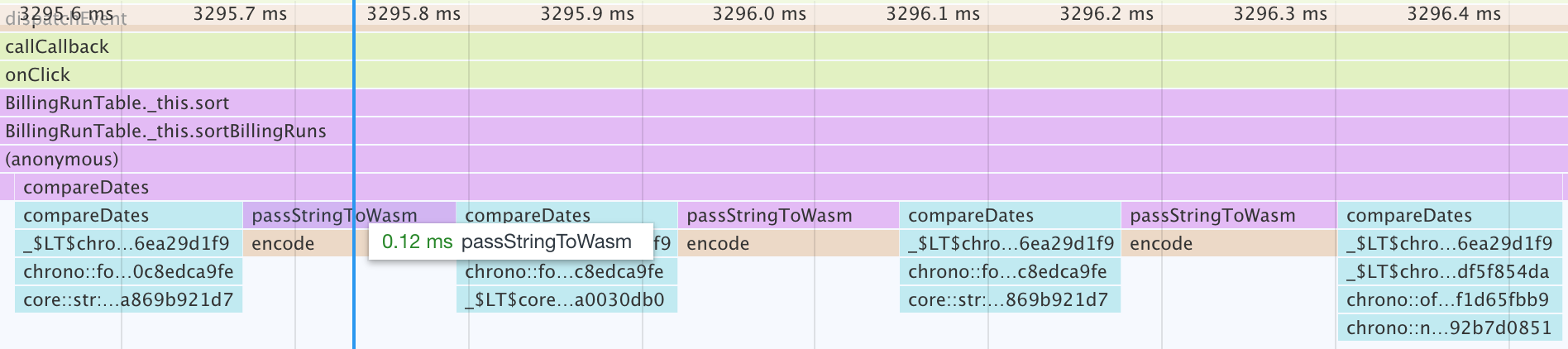

With our very naive implementation, we break rule one…a lot. For each row, we copy one date string from JavaScript’s heap into WebAssembly’s linear memory space to compare it against some other date. Fortunately, with Chrome’s profiling tool, we can see exactly just how expensive this is in practice:

As you can see, the time it takes to run passStringToWasm is roughly the same amount of time it takes to actually run our compareDates function, meaning we spend half of our execution time simply shepherding data into the right place and format. While this naive WebAssembly implementation is still quite fast in the grand scheme of things, there is clearly some room for improvement here.

The right way

So, you might be wondering - if we’re doing things the wrong way, how might we do better? Once again, the Rust and WebAssembly book has answers (quoted text is just under the numbered list):

As a general rule of thumb, a good JavaScript↔WebAssembly interface design is often one where large, long-lived data structures are implemented as Rust types that live in the WebAssembly linear memory, and are exposed to JavaScript as opaque handles. JavaScript calls exported WebAssembly functions that take these opaque handles, transform their data, perform heavy computations, query the data, and ultimately return a small, copy-able result. By only returning the small result of the computation, we avoid copying and/or serializing everything back and forth between the JavaScript garbage-collected heap and the WebAssembly linear memory.

In our current implementation, all of our data lives within JavaScript’s heap, which is currently inaccessible from WebAssembly’s linear memory space (this, too, will be fixed upon implementation of the interface types proposal). As suggested in the quote, a better implementation would instead have our table data and the entirety of our sorting logic reside inside WebAssembly. Rather than hitting an endpoint for the table data from JavaScript, we would do so from Rust, perhaps via some exposed-to-Javascript handle. This precludes the need for any copying, since all of our data now lives and is manipulated entirely within WebAssembly’s memory space.

Without the need to copy, things should be much faster. Problem solved, right? Well, not exactly. We still need all the table data on JavaScript’s end to actually display it, don’t we? Well, fortunately for us, while WebAssembly cannot currently access JavaScript’s heap, JavaScript can access WebAssembly’s linear memory space via the WebAssembly.Memory API. In even better news, wasm-bindgen exports the memory of our WebAssembly instance as a standard module, meaning we can import just as easily as we can anything else.

// From JavaScript, we can easily import WebAssembly's memory.

import { memory } from "../../rust/pkg/wasm_bg";

With this handle, we can then cheaply access our table data via memory.buffer. The Rust and WebAssembly book provides an example of this in their implementation of John Conway’s Game of Life. To save you from scrolling, here’s the code snippet in which they do this:

// Import the WebAssembly memory at the top of the file.

import { memory } from "wasm-game-of-life/wasm_game_of_life_bg";

const getIndex = (row, column) => {

return row * width + column;

};

const drawCells = () => {

const cellsPtr = universe.cells();

const cells = new Uint8Array(

memory.buffer, cellsPtr, width * height

);

ctx.beginPath();

for (let row = 0; row < height; row++) {

for (let col = 0; col < width; col++) {

const idx = getIndex(row, col);

ctx.fillStyle = cells[idx] === Cell.Dead

? DEAD_COLOR

: ALIVE_COLOR;

ctx.fillRect(

col * (CELL_SIZE + 1) + 1,

row * (CELL_SIZE + 1) + 1,

CELL_SIZE,

CELL_SIZE

);

}

}

ctx.stroke();

};

While switching to this paradigm would bring about performance gains versus our current WebAssembly implementation, doing so would require a fairly significant restructuring of our app, and we have already solved our immediate performance problem in a much simpler way via the native Date API. This blog post is also probably long enough as is…

Random ending thoughts

We covered a lot throughout this post, from native JavaScript Dates and standard date formats all the way to the nitty gritty details of implementing a portion of our sorting algorithm in Rust and WebAssembly. In its current state, WebAssembly is a very powerful tool; we achieved a significant speedup with an extremely naive replacement of our date comparison code. However, as we touched on throughout the post, WebAssembly is nowhere near complete. There are a multitude of in-progress proposals that will unlock vastly more performant and ergonomic workflows.

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions or comments, feel free to leave them below. Also, if you want the chance to work with some cool people and some cool technology, come join us!